Introduction:

There are some careers, no matter how meritorious, that will never make it into the Hall of Fame. There’s an argument for Tim Thomas to be in the Hockey Hall of Fame, with his two Vezinas and 2011 Conn Smythe1. He was undoubtedly one of the best goalies in the NHL between 2005-06 and 2011-12. But even those years of dominance, I’d argue, aren’t enough.

Some careers don’t get the respect they deserve due to an overemphasis on playoff performance. We can think of playoffs as an annual second season designed to determine the best team of that year. But when evaluating careers worthy of a place in the Hall of Fame, I believe playoffs are mostly irrelevant — something that can, at best, boost a borderline case. But the majority of hockey is played in the regular season. And to turn our noses up at performances that just so happened to be on non-playoff teams —especially when evaluating goalies — does this sport a grave disservice.

This brings us to Tomáš Vokoun. Vokoun only played in the postseason thrice: 2003-04 and 2006-07 with the 8th- and 4th- (respectively) seeded Nashville Predators, and once with the 1st-seed 2012-13 Pittsburgh Penguins.

But playoffs aren’t what we’re here to talk about today. We’re here to talk about the part of the season all players get play year-in-year-out.

Span of Dominance

Tomáš Vokoun never won a Vezina. And unlike many other goalies for whom that is notable, he was never snubbed for a Vezina.

But Vezina’s aren’t what makes Vokoun’s Hall of Fame case interesting. It’s the fact that, for a 6-season peak — from 2005/06 until 2010/11 — Tomáš Vokoun was 15% better at preventing goals than the league average goaltender.

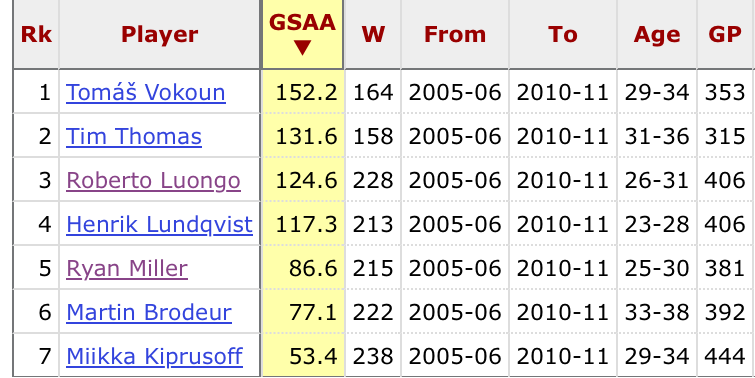

You know who was better than him? Well, let’s do a who’s who of that era.

Vokoun vs the Post-lockout Vezina-winners

For the 6 years following the lockout, the Vezina winners were as follows: Miikka Kipprusoff (05/06), Martin Brodeur (06/07 and 07/08), Tim Thomas (08/09 and 10/11), Ryan Miller (09/10), and to round it out Henrik Lundqvist who won the year following this span and Roberto Luongo who was in top-10 voting multiple times and was snubbed in 03/04. These goalies make up the cream of the crop post-lockout.

But how does Vokoun compare? Well, a good way to compare is to look at Goals Saved Above average. This is a stat that takes a goalie’s Save percentage, multiplies it by the number of shots faced to get goals allowed, then compares it to how many goals a league-average sv% would have yielded at that many shots. If you’re above league average, you accumulate positive GSAA; if you’re below average, you get negative GSAA. If you’re really above or below average, you get more/less GSAA than someone who is closer to average.

Put simply, Vokoun has the most GSAA of any of the best goalies in the 6 seasons following the lockout.

Despite his remarkable 05/06 Vezina win (74 GP, 78 GA%−, 41.6 GSAA), Miikka Kipprusoff never reached the same heights as that season — registering three seasons of below-average save percentage throughout the span in question. He was, however, a heavy-workload starter, much in the mold of Martin Brodeur, who despite back-to-back legendary seasons in 06/07 and 07/08 fell back down to earth following those seasons. Of course, “falling back down to Earth” for Brodeur is putting up sub-20 GSAA seasons. His 2010-11 was particularly bad, however — and not just by Brodeur standards — with a GA%- of 110: that is 10% worse than league average.

Ryan Miller, like the previous two goalies, experienced one season of above-100 GA%− — a still-respectable 103 GA%− in a 76-game 07/08 on a bad Sabres team — but other than that, was well above league-average with his 08/09 (59 GP, 89 GA%−) and Vezina-winning 09/10 (69 GP, 81 GA%−) standing out, in particular.

Henrik Lundqvist was brilliant on either end of this span. His rookie 05/06 (53 GP, 79 GA%−) and sophomore 06/07 (70 GP, 88 GA%−) seasons stand out, as do his 3-season stretch of 08/09-10/11 (211 GP, 90 GA%−), which are comprised of two 89 GA%− seasons and one 91 GA%− season. Consistent brilliance is Hank’s calling card. That and handsomeness2.

Roberto Luongo, like Hank, didn’t win a Vezina during this span, but much like Lundqvist and Vokoun, did everything but. Luongo had 3 seasons of above-20 GSAA: a mark he cleared handily each time with 32.6 in 05/06 (75 GP, 87 GA%−), 34.2 in 06/073 (76 GP, 83 GA%−), and 26.7 in 10/11 (60 GP, 83 GA%−). The 2.9 GSAA he accumulated in his 09/10 (68 GP, 98 GA%−) ‘downyear’ — during which he was the starting goalie for the Canadian Olympic team— is really what prevents him from surpassing Thomas on this list.

The aforementioned Tim “bit-of-a-late-bloomer” Thomas is really just as dominant for this stretch as Vokoun, but in a different, more highly-concentrated way. For starters, Thomas wasn’t one coming out of the lockout: he played only 38 games (84 GA%−) in 05/06 — well, 2006 really. His game logs for 05/06 reveal a starter’s workload of playing every 2nd or 3rd day until February 11th, before eventually resuming that workload sometime in March. He was exactly league average the following season (66 GP, 100 GA%−), but really put it together in the following season with a 21.3 GSAA (57 GP, 86 GA%−). The two highlights of this stretch are his Vezina-winning seasons of 08/09 where he played in 54 games sporting a 74 GA%− with a GSAA of 41.0, and 10/11 where he played in 57 games sporting a 71 GA%− with a GSAA of 45.8. Before we give due praise to another ‘Thomas’ — the one without the ‘h’ — do me a favour and reread those statlines. Those were the two best GA%−’s this side of Hašek’s run of Vezinas until Shesterkin’s Vezina season in 21/22 . Again, in an age were goalies could still go for 70+ games of quality goaltending, Thomas was by no means a workhorse, but he still was a headache for the opposition every time he was in net.

And now, for the main attraction. Click here to see the exact stats.

Tomáš Vokoun had six seasons in which he was at least 10% better at preventing goals on a rate basis than the rest of the league. No one else replicated that over this span. Not any of the Hall of Famers, not the multiple Vezina winners, no one. When I evaluate goalie seasons, I want to see two numbers to really wow me: a GP greater than or equal to 60 (if we’re talking pre-2010s), a GA%− less than or equal to 90, and a GSAA 20 or above. Vokoun met at least one of those in all 6 of his seasons. during this span.

But now that we’ve established that Vokoun had a dominant stretch, let’s see how this stacks up against goalies throughout the last 30-40 years.

Who has had a Better Peak?

Tomàš Vokoun played 353 games between 05/06 and 10/11 over which he had a GA%− of 85. To raise Mel Lastman’s famous question, “Who [was] better?”

Well, a couple of goalies have had better spams than Vokoun’s.

Let’s start with his fellow countryman, Dominik Hašek, who had a 72 GA%− across 364 games from 93/94 until 98/99. Remember how I was drooling over Tim Thomas’s Vezina seasons? Hašek basically had 6 seasons of that, winning 5 Vezinas. I believe he should gotten all 6, but that’s a different article.

We’ll move onto the next obvious candidate: Patrick Roy, who had a GA%− of 80 across nearly 400 games from 87/88 until 93/94. Mind you, Roy had an 85 GA%− for his entire career, so if you ever need a good comparison to contextualize Vokoun’s post-lockout stretch, he was basically Patrick Roy.

Speaking of equal to Vokoun, Martin Brodeur had an 85 GA%− over 301 games from 93/94 until 97/98.

Roberto Luongo during his first stint in Florida (00/01-05/06) also posted a GA%− of 85 over 317 games — a rate he maintained if you include his next season, 06/07, which was his first in Vancouver, and brings the total games played to 393.

Cujo had an 82 GA%− during his 6-year tenure with the Blues from 89/90 until 94/95 during which he played 200 games.

On this side of Vokoun’s career, Tuuka Rask maintained an 85 GA%− over 261 games between 10/11 and 14/15.

Of current goalies with a chance of replicating Vokoun’s 6-season, 350+ games played, 85 GA%− peak, there’s Igor Shesterkin with a career 84 GA%− in 213 games, Linus Ullmark with an 84 GA%− in 184 games since 19/20, and that’s it. Not Vasilevskiy, not Hellebuyck, not Sorokin, not Swayman. The last four still could, but they’d need to post GA%−’s below 85.

So, Vokoun’s span of dominance was only bested by three of the best goalies of all time, while 3 goalies came close to replicating it, but didn’t do so in as many games. And currently only two goalies are on track to replicate 85 GA%− over 6 seasons, but that could change as early as next year.

I’m sure I could also find spans by Esposito, Plante, Dryden, Parent, and maybe Bower that also eclipse this span of dominance, but the 60s-70s were kinda weird with regards to league parity and I’m a bit suspicious of some of those GA%−’s, but that’s not today’s topic.

If you’re wondering what the point of all that was, it’s this: Vokoun’s peak was elite. It’s better than Belfour’s peak, for example. It’s better than a lot of other great goalies’ peaks. I’m sure if you rearranged some of Price’s down years, you could recreate this peak in his sample. But Price and Marc-Andre Fleury — two of the assumed next three goalies to go into the Hall of Fame — didn’t have their best seasons consecutively. Rask — the other of the three goalies — had some consecutive seasons that were Vokoun-like by rate, but not by volume4. Only Vokoun’s peak, since the beginning of the salary cap era, was so prolonged and so consistent.

The non-Peak Years

Now, as I mentioned off the top, I don’t believe Tim Thomas — who had a similar, albeit more extreme, peak as Vokoun — should be in the Hall of Fame, but if all this article does is convince you that he should, I guess I’ll take that. Because Thomas did have a HOF-worthy peak, but he didn’t have much else. Vokoun, by contrast, did.

The start of Vokoun’s career was a single, 20-minute appearance in Montreal. He allowed 4 goals. Not a good start. Left unprotected, he was selected by the Predators in the 1998 expansion draft. He went on to be the 1B of Nashville’s goalies tandem for 4 seasons along with Mike Dunham.

In 1998-99 and 1999-00 he played near-identical seasons: Vokoun played 37 games in the former, 30 games in the latter, with a 100 GA%− in each. 2000-01 represented a step forward with a 96 GA%− in 37 games and 2001-02 represented a step back with a GA%− of 106 in 29 games.

After this stretch, he became Nashville’s starter and workhorse. He very well in his first season, posting a 90 GA%− in 69 games. Second season, he was less effective, dipping a bit below league average (102 GA%−) , but offering 73 games played. This isn’t bad, per se. Marty Brodeur, Ryan Miller, and Miikka Kipprusoff each have posted seasons of similar workloads and results. Playing 70+ games as a goalie is tough. What also makes this season special is that it was his last with a below-average SV% in his career.

Fast forward to after his peak, Vokoun played one season in Washington and one in Pittsburgh. In his 2011-12 season in Washington, he served as the team’s 1A, playing over half of all possible games (48 GP) for Washington, despite injuries and inconsistent play, still finishing over league average in his save percentage (GA%−: 96).

In Pittsburgh, he was the backup to Marc-Andre Fleury during the lockout-shortened 2012-13 regular season (GP 20, GA%−: 92). He was still backup before taking over as the starter 3 games into the playoffs. After closing out the first-round series vs the Islanders — the first series win of his career — he backstopped the Penguins to a 5-game victory over Ottawa only to be swept by the Boston Bruins in the Conference Finals.

Unfortunately, though he was set to return to Pittsburgh for another season, he was diagnosed with blood clots in the preseason, which forced him into retirement.

Among goalies with more than 630 games played, Tomáš Vokoun sits 8th all-time in GA%− for his career with 90.3, tied with fellow Panthers legend Roberto Luongo.

Why I Think Team Success is Irrelevant (to Goalie Analysis)

What of the n-1 (teams) who don’t win the cup each season?

Aside from a rough night in a Habs jersey, when Vokoun entered the NHL (in earnest) the league had 28 teams, which was soon increased to 30. It remained at that number for the rest of his career. Statistically, only 1 team out of the 30 won the Stanley Cup annually — to this day, that numerator hasn’t changed even if the denominator has. But what of the rest of the n-1? Are their seasons and stories and successes not also the fabric of the history of hockey? Are the games of non-playoff teams annually struck from the record books? Are the performances of players outside the postseason cast aside and never looked at again, or is that merely what we choose to do with them sometimes?

When it comes time to tell tale of the great teams in hockey history, let us speak of the great teams. When it comes time to do the same for great players or seasons, let us not similarly speak only of the great teams.

Now that I’ve sufficiently waxed philosophical about the issue — and exceeded my rhetorical question quota — let’s look at this from a more technical perspective.

The win condition of a hockey game is to outscore your opponent… Goalies, thus cannot directly help their teams win hockey games, but merely hinder their opponents’ efforts to win.

To win a hockey game you must score more goals than the other team. Ground-breaking stuff, really. I wonder if anyone else has thought of this. Put snappier, the win condition of a hockey game is to outscore your opponent.

At your disposal to help with this are 3 forwards and 2 defensemen. Despite comprising 83.33% of all players on a the ice at even-strength, these positions have scored roughly 100%5 of all goals in NHL and organized hockey history. That’s because 1/6th of the players on each time are dedicated wholly to preventing goals. Now, goalies disproportionately influence the outcome of a game compared to any single one of their teammates, but they can only do so by preventing the other team from scoring (i.e. winning). Goalies — by the strictest wording of the win conditions — thus cannot directly help teams win hockey games, but merely hinder their opponent’s efforts to win.

You might argue that the two are equivalent: a goal saved is as good as a goal scored6. To which I say:

NOT IN A TIE GAME, IT’S NOT!

NOT WHEN YOU’RE LOSING, IT’S NOT!

— me, the author of this article, literally screaming as I type this

Let’s walk through both scenarios

Scenario: Your team is tied

Your goalie makes a save.

The game is still tied.

Your team will not win the game unless…

Your team scores

Your team is now winning

Scenario: Your team is losing

Your goalie makes a save

Your team is still losing

Your team will not win unless…

Your team team scores at least 2 more goals

Scenario: Your team is winning

Your goalie makes a save

Your team is still winning

Your team will not lose unless…

The other scores enough goals to tie the game (see scenario 1)

At the end of the day goals win games.

This does not diminish the importance of goalies or of goalies playing well. Carey Price made a career out of making his offences look better than they actually were. But that’s a very indirect — and often unsustainable (cf. the Habs in the 2010s) — way to run a hockey team. But as I point out in my Shutout Paradox article, the best goalie outcome — a shutout — can only be a non-loss. Goalies cannot win games by themselves because they can’t/don’t score.

And this is why I fight hard for guys like Vokoun. They were tasked with helping their teams win in the least direct, but most consequential way. Vokoun held his end of the bargain. He shouldn’t be forgotten, nor his achievements and play made lesser because the guys in front couldn’t do their jobs. Fundamentally, this is a universal goalie experience: doing your best and still losing. It sucks. It’s life. But due to the competitive fire that’s within all those guys we make play games for a living, it can produce some of the most memorable performances.

Looking at the Florida Panthers specifically, where Vokoun spent most of his span of dominance, we see that the crux of my above analysis play out time and time again.

Hockey youtuber Ben Oakley said this of Vokoun in his video titled “How to trade for a superstar goalie and somehow get worse (The 2007-2011 Florida Panthers)”:

Every night, [the 2011 Florida Panthers] would march out the only man who could win them games

Indeed many nights, he couldn’t even do that! Not for lack of his trying. Oakley further details a particular “stretch in late January [2010]” wherein,

Vokoun shutout the Atlanta Thrashers in a win. Then gave up 1 goal [plus an empty-netter] as the Panthers were shutout by Marin Brodeur and the Devils. Then, in the next game, gave up 1 goal to the New York Islanders in a shootout loss. Then, [Vokoun] realized his team could only win if the other team didn’t score and pitched a 39-save shutout against the Leafs.

4 games. 2 goals against. Florida’s record: 2-1-1.

Do yourself a favour and click that video link. Or this one (it's the same link). It’s basically what inspired this post.

Conclusion

Look, I know I’m screaming at the void. The selection committee is a closed circuit — of both communication and ideas. And if the oft-argued cases of Curtis Joseph and Alexander Mogilny fall annually on deaf ears, then certainly this veteran of 22 playoff games, winner of a mere 2 playoff series, never-winner of a Vezina will never get the call to the Hall. And I’d agree with that statement: Tomàš Vokoun will likely never be Hall of Famer. For goalies alone, Curtis Joseph and John Vanbiesbrouck both have stronger claims, both from traditional avenues and whatever path I’m whacking through the foliage of statistics.

This is reality. But I persist.

Because as much as I believe that Vokoun’s career is Hall-worthy — though perhaps a “mid-to-outer-circle”—his case represents a rejection of conventional surface analysis that over-rewards team success, individual awards, and playoff runs. Vokoun’s case is built on the idea that someone who was consistently among the league’s best (which Vokoun was — in consecutive seasons, no less7) — and above-or-close-to-average for the rest of their career deserves to be in the Hall of Fame, regardless of lack of team success.

It’s my personal opinion that the goalies we should be celebrating are the ones that make opponents think, “ah, f___! Not this guy”. And given the low rate Tomàš Vokoun allowed goals during his peak — despite playing for only playoff team during that time — I infer that he was thus complimented a lot.

Not to say that Conn Smythes should be weighed too heavily in Hall of Fame cases. It’s bad enough Vernon got in, and if they induct Ron Hextall or — heavens forbid!— Bill “innings eater” Ranford, I don’t know what I’d do!

If you open your dictionary to ‘handsome’ and don’t see Henrik Lundqvist’s face, consider throwing away your dictionary. It’s broken.

The same year he finished runner-up in both the Hart and Vezina. ‘How’, you may ask. Simple. Two voting pools. The Hockey Writers pick the Hart and the GMs pick the Vezina. To be honest, I think they both got it right.

i.e. Thomas-like. How fitting. Boston really has had some of the greatest goalie tandems this side of the 05 lockout.

Goalie goals are exceptions that prove the rule.

Truly, Ben Franklin’s assertion that “a penny saved is a penny earned”, is spoken like a man who never had to pay income tax.

This is by no means a guarantee. Both Carey Price and Marc-Andre Fleury — presumptive Hall of Famers — have dominated for seasons and struggled for others. Sergei Bobrovsky is another contemporary example of this.

I entirely agree with this! Sports fans tend to really (really) overrate the importance of playoff performances, when in fact the regular season is what contains the vast majority of the game being played, and should therefore be weighed much more heavily than the playoffs are.

Guys like Tomas Vokoun always seem to get passed over for Hall of Fame, regardless of sport. Never the best when looking at one season, but the best when looking at six season stretches, is just not a good way to get in, because HoF voters love to overrate the importance of themselves, giving big weight to the end of season awards, voted on by themselves. In a way, it's like corruption. I run into this several times in my (American) football work as well.

Good on you for fighting the good fight! Tomas was a great player. It's not his fault he spent his whole career on less than stellar teams, and the memory of his career deserves to be kept alive.